The studio was a dark place when I first saw it, almost two years ago. The light fixtures were ancient, and many fluorescent bulbs were burnt out. The landlord had stored hulking old machines there, since Charlie had stopped using the space. Half the walls were unpainted, dingy brown drywall. Dust and dirt and rat droppings had collected in corners and on shelves.

And everywhere – piled on tables, buried in wooden crates and plastic bins, tucked in deep cubbyholes – there were chunks of glass.

That’s how they seemed – just chunks. Lying there in the studio, unseen, unknown to anyone but Charlie.

He had left many of his sculptures unfinished.

Cast glass always requires some finishing work, and it is usually tedious and time-consuming. Hours and hours of grinding smooth the rough edges, sandblasting away remnants of plaster, polishing surfaces to a shine. These steps are called coldworking, and often it takes as much time as the creation of the cast glass itself.

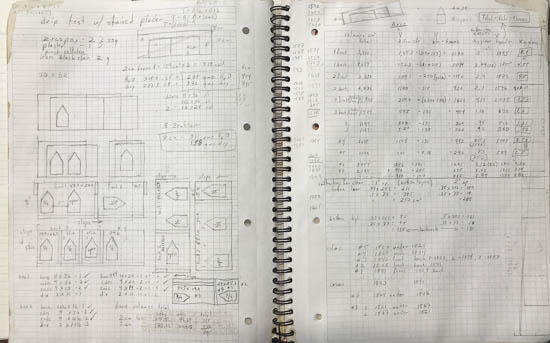

Charlie loved all that went into the design of a piece and preparation of glass for the kiln. He was extremely precise with his measurements and calculations for making a mold and determining how much of each color of glass would produce the effect he wanted. He loved the science that produced the art.

But coldworking? Not so much.

Charlie told me that he would never fire the kilns again. He really wanted to complete some of his cast pieces, but the labor was too much for his chemo-reduced energy levels. I tried to help him find a coldworking shop where we might ship the pieces. No luck.

I thought about doing some of it myself. I had learned to use the equipment, and for the most part it didn’t seem too hard. Charlie and I agreed that, despite the drudgery of coldworking, if you relax into the rhythm of it you can achieve a kind of Zen meditative state.

But I was terrified that I would mishandle, ruin or break a piece.

And the time it would take… I just didn’t have enough.

One restless night, the solution suddenly came to me: glassblowers. They have to do coldwork, too. With the economy at a near-standstill, surely someone at a local glassblowing studio would be available to coldwork Charlie’s pieces.

That’s how I found Nicholas Folz. A sculptor and glass artist with a BFA from University of Wisconsin, he moved to Atlanta last fall to work at Decatur Glassblowing. Right now, though, there isn’t enough work to fully occupy all four employees.

From his first moments, Nick was at home in the studio. We spent quite awhile talking about Charlie’s intent, techniques, and how best to show them with the coldwork.

Nick considers it a privilege to work on Charlie’s sculptures. It’s also daunting, for both of us – not only the technical challenges, but to interpret and complete another artist’s work.

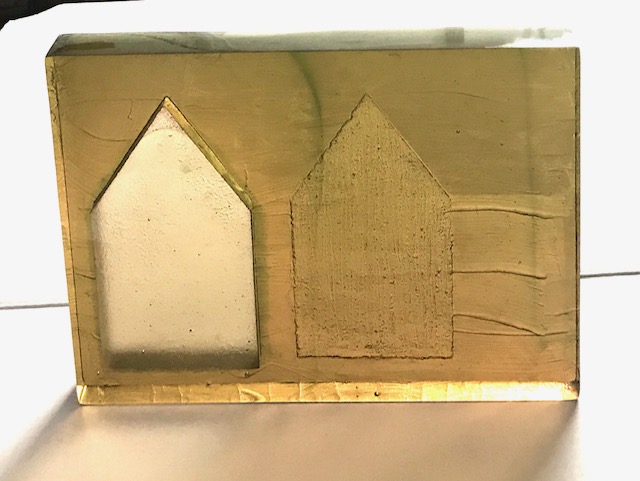

In the first week, Nick completed three pieces. We were both amazed at the transformation.

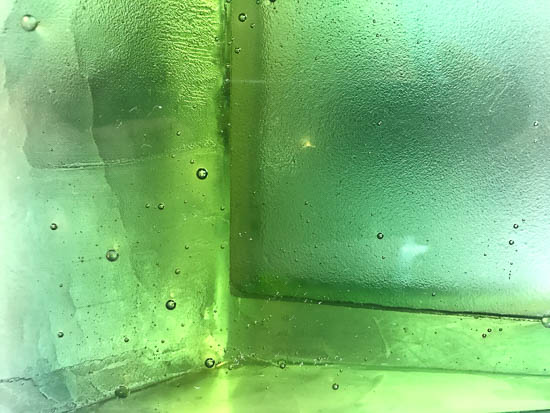

With surfaces ground and polished, much more light can pass through the glass. Details glow, colors shift, new dimensions are revealed.

We stood and watched the light coming through what had been a simple block of amber glass. Now we could see an element of green running through the two house shapes.

“Look at that!” I exclaimed. “That green wasn’t even visible before. There’s so much going on in this piece. Who knew!”

Nick looked up at me. “Charlie knew.”

And now we know, too.