Gen. Eisenhower really needed something for his men: 3 million bottles of Coca Cola. And bottling plants to refill them.

Eisenhower’s requisition was sent to the Coca Cola company on June 29, 1943. Robert C. Woodruff complied.

He set up dozens of bottling plants across Europe, and U.S. servicemen were able to buy Coke for a nickel, Coke’s history proudly says:

Over 5 billion servings of Coca-Cola were distributed to U.S. troops during the War.

I learned this story not at the Coke Museum in Atlanta, but at the George C. Marshall Museum in Lexington, Virginia.

The original paintings that became Coke ads, like the one pictured above, were in a special exhibit called “What We’re Made Of.” The exhibit “looks at the contributions of civilians and industries on the home front to the American war effort.”

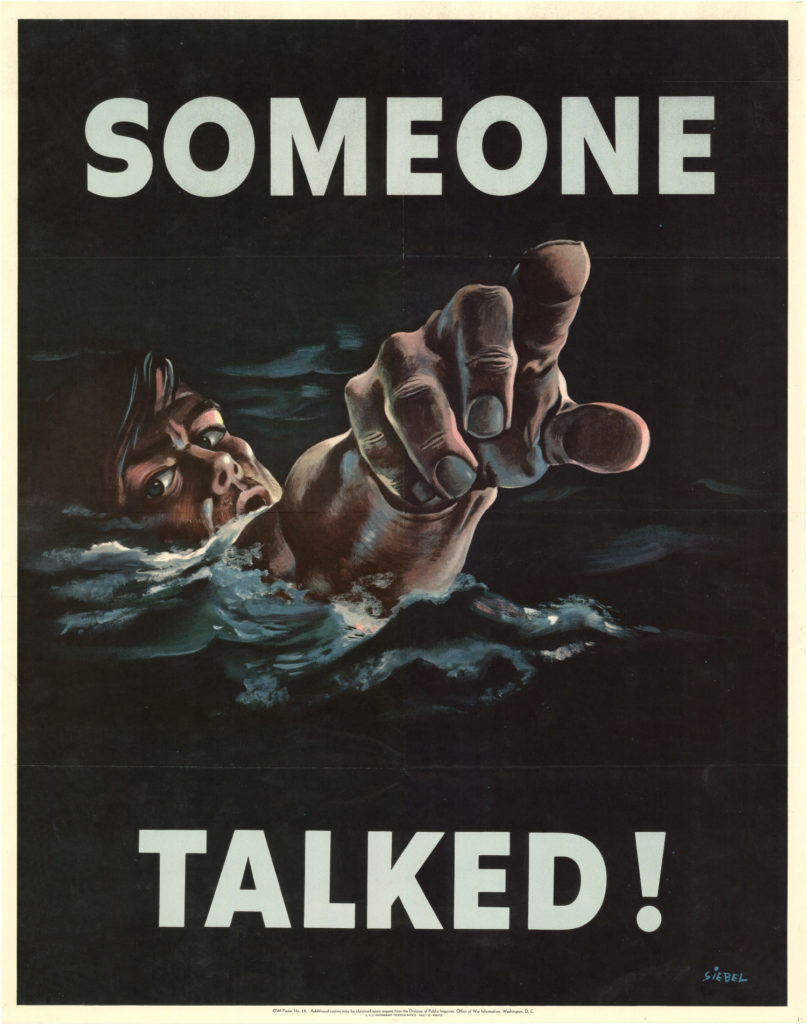

A fine collection of war propaganda posters drew me in with their emotional impact. Love the chilling drama of this one:

I pondered the connection between “loose lips sink ships” and industrial products like Coke, Hershey’s Tropical Chocolate bars and Hormel’s pork product, Spam.

The exhibit didn’t include cigarettes, which were distributed in rations to soldiers from World War I to 1975. That turned out to be more controversial than Coke.

The success of these companies wasn’t built on altruism, but America’s intense loyalty to these brands was loaded and locked during the war. Coke, Hershey’s and Spam were locked into the tastebuds and collective memory of soldiers and their families at home – part of the time when we won a great victory against a common enemy.

George C. Marshall had been working since 1938, as Deputy Chief of Staff, to gear up the Army’s equipment and supplies. Industrial production had to be mobilized and sped up.

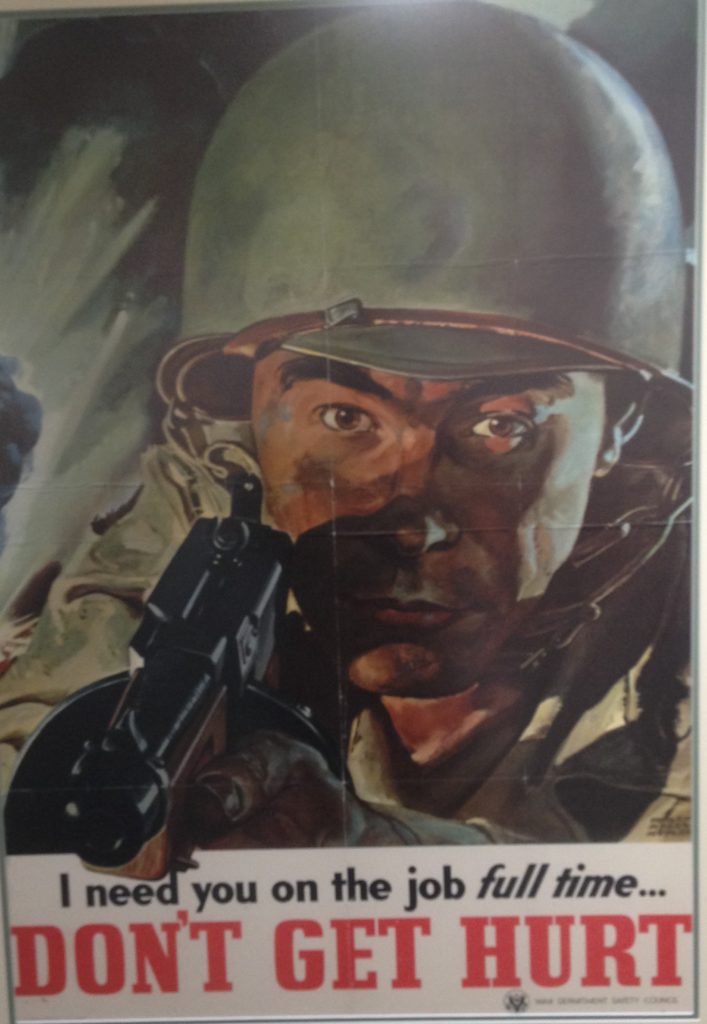

War posters exhorted Americans to do whatever they could to support the industrial production needed for the war.

CAN ALL YOU CAN – It’s a real war job! said a poster encouraging people to grow and can their own vegetables and fruit.

A soldier looks at workers straight in the eye, pleading with them to be safe on the job:

Hard work was elevated to patriotism in the Victory Creed – I shall be regular in my attendance because every unnecessary day I take off is a red letter day for the enemy… I shall be careful in my work so that neither waste nor delay shall endanger the life of a Navy man….

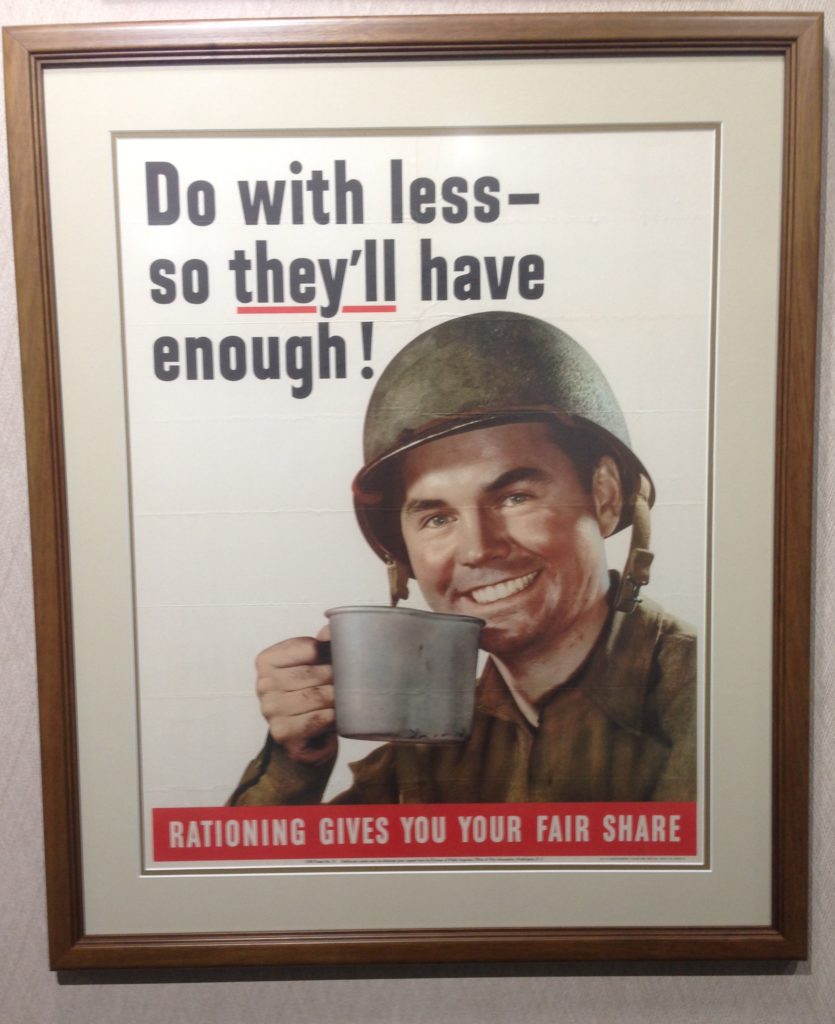

Rationing was portrayed as a proud burden for a woman, her arms laden with groceries and parcels, while behind her, shadowy soldiers march with heavy rucksacks and guns. I’ll carry mine too! the woman declares. And beneath, the reminder: Trucks and tires must last till victory.

The larger goal was always made personal.

The effort of an individual in the U.S. was always tied to the success of a soldier on the front lines.

Employment of women and African Americans wasn’t promoted as a gain for them, but as a contribution to the common goal.

The more women at work, the sooner we win, says a poster with a young Rosie Riveter type.

Twice a patriot! proclaims a poster of a one-armed African American man. It tells how he lost his arm at Pearl Harbor but is now working as a welder in a West Coast shipyard.

Industrial production for the war ended the Great Depression in America, and led to a period of tremendous prosperity and growth of the middle class.

George C. Marshall understood that long-lasting peace required a solid economic underpinning. The Marshall Plan, 1948-52, rebuilt Europe.

How will we rebuild America now?

Today’s penny is a 2001, the 50th anniversary of the end of funding for the Marshall Plan.

Excellent post.