Clouds of small insects floated above our heads. They didn’t try to bite us.

Tom and I were kayaking on the lake. We stopped, floated, and watched them. They were too small and fast to identify – they were smaller than mosquitoes, a little bigger than gnats:

As we talked to each other about how beautiful the day was, we noticed that the bug swarms moved in a loose unison.

Their movements reflected the cadence of our words.

They weren’t close enough to be affected by the air currents of our speech. We even tried blowing air at them, with no effect.

But when we spoke, they bounced along in time. Especially when we spoke in high-pitched tones.

It was mesmerizing to watch. And you have to wonder: What could this behavior mean?

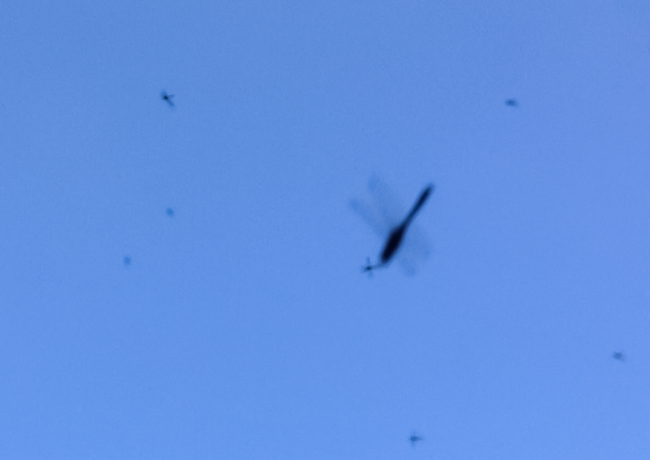

The lake had plenty of dragonflies, too, and they were attracted to the swarms of bugs.

We watched the dragonflies as they fed on the bug clouds. They didn’t seem to be aiming for any one insect. They flew in triangular or spiral formations and scooped up whatever was in their path.

It occurred to me that those clouds of insects were simultaneously reacting to sound waves as a form of self-defense.

Dragonflies are fast, and their wings make a sound that is high-pitched.

If the insects move – in any direction – when they perceive the sound of dragonfly wings, their odds of being eaten decrease.

So they weren’t really engaging with our fascinating conversation. They were just reacting to sound waves.

And the dragonfly, by scavenging in a pattern rather than aiming for a particular bug, might have improved his odds, too.

Either way – bug dinner was a moveable feast.

Today’s penny is a 2012. In that year, a Brazilian radio station won the Grand Prix at Cannes Lion for a marketing campaign in which it broadcast high-frequency noise under its music as a mosquito repellant. Scientists say the method doesn’t work.