The image above comes with this caption:

Typical group of Gary, Indiana school children. Top row standing : left to right, Greek, Negro, Roumanian, Lithuanian, Italian, Polish, Croatian, Hungarian. Middle row, American, Austrian, German, Bulgarian, front row, Scotch, Russian, Irish, Assyrian, Slavish, Jewish and Spanish.

Do these children look American?

The people in the photo above were captured before 1920, in a time that America was awash with immigrants. Look: Do you see yourself? Or your grandmother?

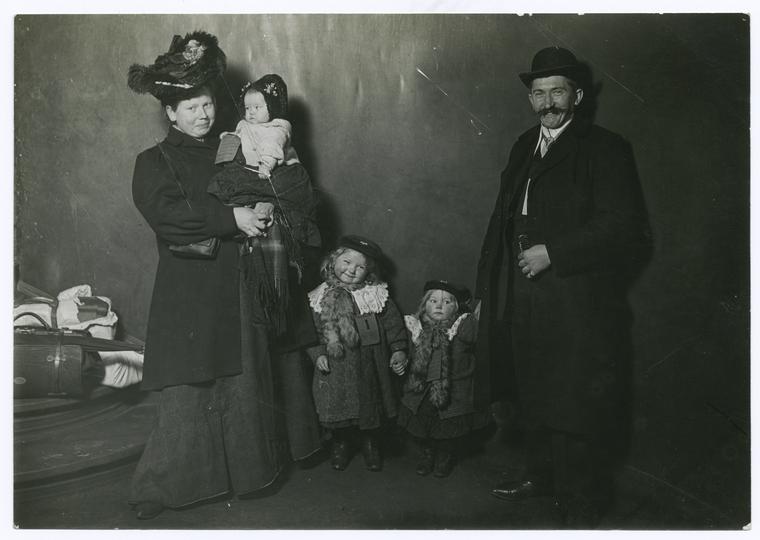

The German immigrants in the next photo, below, aren’t related to me, but they could be.

Look how scared their little girl in the middle is, and the eyes of the almost-daring-to-be-happy father:

And this one – the catalog says they’re Germans, but couldn’t they just be anyone? Hungarian, Russian, Mexican?

All three photos are from the huge collection that the New York Public Library recently put online and made easily accessible because the photos are in the public domain. NYPL takes that seriously – they understand “public domain” isn’t just about copyright, but that it should also mean ‘easily used by the public’.

They’ve put 180,000 digitized images online. Search just about any topic you like, and there are photos of it.

Perusing the immigrant photos reminded me suddenly of a book edited by Edward Steichen, “The Family of Man,” in which people from around the planet were featured doing normal human things – eating, laughing, having babies. There were 273 photographers involved in the exhibit that the book was based on, in the ’50s.

The book caused a bit of a stir, I think, because it included photos of a live birth (click this link to see one of the photos – they are NOT in the public domain).

Hailed as the most successful exhibition of photography ever assembled, The Family of Man opened at The Museum of Modern Art, New York in January 1955. This book, the permanent embodiment of Edward Steichen’s monumental exhibition, reproduces all of the 503 images that Steichen described as “a mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world. Photographs made in all parts of the world, of the gamut of life from birth to death.”

I looked at this book over and over when I was young. Partly because it revealed images of the things I wasn’t supposed to ask about – sex, birth, nakedness.

But also because it was filled with people who didn’t look like me or my parents in the shape of their features, but looked exactly like us in expression and emotion.

Thinking about that book today, I realized how much it had affected me. How powerful images are, especially when we are young. I saw beauty in those faces, I saw myself and my own family, and it taught me something about shared humanity.

Today’s penny is a 1996, the year of the reissue edition of “Family of Man” that I just bought a used copy of.