Catalogs that come to my mailbox usually get dumped straight into the recycling bin, but today I took a cruise through Shutterfly’s.

There was something strange about the catalog, though. It took me awhile to figure out what it was. And then I realized: It’s not what it is.

It’s what it isn’t.

A 24-page catalog, and a 16-page gift guide insert, that apparently isn’t meant for black folks.

You will look long and hard to find any black skin in all of those photos on all those pages. I finally found one, a small black child in a tiny photo of a biracial grouping.

There were a few people in the catalog who were vaguely Asian, and some people who might be biracial or maybe just have a good tan. But dark black skin was nowhere to be seen.

Maybe you’ll say this is a small thing, compared to the police brutality and racial slayings that are still happening in America.

But it isn’t, to me. Images are powerful. Shutterfly’s catalog is all about family at the holidays.

How is it possible, with all the people who must have worked to produce that catalog, that none of them chose a photo of an African-American family?

I know, I shouldn’t be surprised. This year alone has been rife with examples of misuse and absence of black images. Not to mention Google’s identification of black faces as “gorillas.”

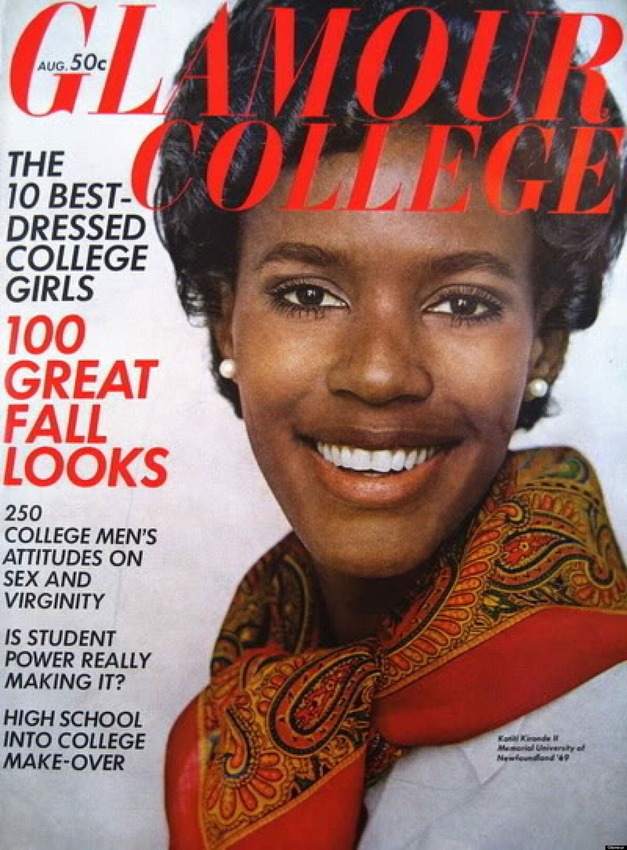

Although black men – entertainers and world leaders – showed up on U.S. magazine covers as early as 1930 (Time), mainstream magazines have been extremely slow to feature black female models.

GQ waited until 1996 to feature a black woman on the cover, and Vanity Fair and Cosmopolitan have had just a few in the past two decades.

Shutterfly, though? What, do they think African-Americans don’t like to take photos and show them off and make gifts for their friends?

Maybe the Shutterfly staff is just dreaming of a white Christmas.

And their catalog is now in my recycling bin.

Day 127’s penny is a 1974, the year of the first American Vogue issue to feature a black woman on the cover.

Boycotting Shutterfly