Since I was a kid, any time I’ve taken an aptitude test I score higher on math than language. My GRE score was highest in analytical, almost as high in quantitative reasoning, and lowest in verbal reasoning.

Funny stats for someone who always wanted to be a writer, and whose career involved very little math.

There’s been a revived discussion in recent years about women in science, technology, engineering and math professions (STEM). It’s made me wonder why I didn’t go into math or science.

I can’t claim that I wasn’t encouraged. My parents and teachers gave me praise and attention for all my academic accomplishments. Yes, my mother had a math phobia, but Dad sure didn’t, and I didn’t feel that Mom’s issues had anything to do with my academic work.

True, my classmates made fun of me for being smart, but I don’t think it was anything in particular to do with math. In fact the insult that stung and bewildered me most was being accused of reading the dictionary because I had such a vocabulary. Well, what about it?

I went to a small Catholic high school, with barely more than 400 students, so there wasn’t a great selection of classes. But when a group of us got bored in algebra, the teachers created a separate advanced math class just for six kids – and it was led by a female student who was a senior.

Same with biology – I was allowed to take advanced biology as a junior, a class that was normally for seniors only, and taught by a woman.

Such encouragement, in the midst of “women’s lib,” was part of a larger trend.

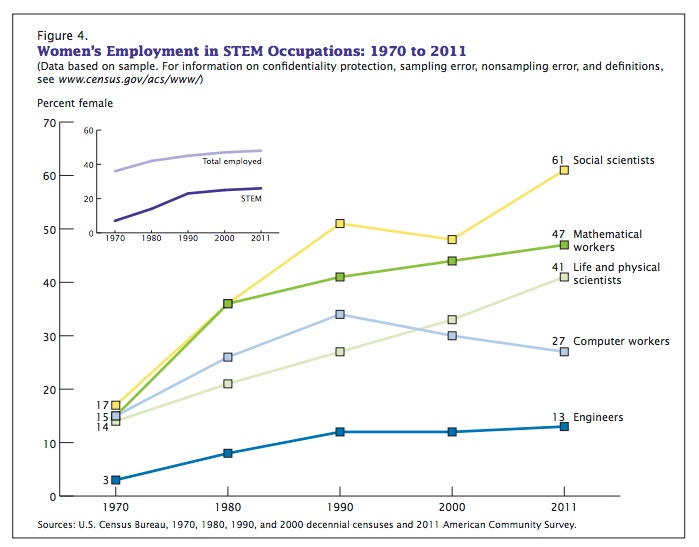

“Most of the growth in women’s share of STEM employment among those under the age of 40 occurred between 1970 and 1990,” according to a report by the U.S. Department of Commerce.

On the other hand, I didn’t know of any interesting jobs in those fields. I knew I didn’t want to be a doctor or an accountant; I didn’t know there was anything else you could do with math and science.

My true love was for writing. I’d been writing poems since I was 7 years old, and I wanted to be a novelist. I loved writing because it gave me an emotional outlet – a way to express all I felt, and to share the beauty that I saw.

Which is stereotypically female, I know.

The funny part is that I chose journalism as my college major because it was a practical way to be a writer. I guess I didn’t realize that the professional standards of journalism would strip my writing of both feeling and beauty.

Newsrooms were still male-dominated in 1980, but I ended up being the math tutor in the newsroom whenever another reporter was scratching his head about the city budget or student test scores. I would be retiring now if I had a dollar for every time I explained how to calculate the percentage increase and decrease.

I’ve loved new technology since I first switched to a CRT from an IBM Selectric, and have been helping friends and family with their computer problems ever since. My frustrations with technology are mostly because I don’t have enough time to learn everything that I’d like to.

In doing media development overseas, I realized that I liked to track project spending and work with spreadsheets. It was a bigger, more animated version of my lifelong tracking of my own expenses down to the penny.

And what could be more fun than figuring out how to measure what we accomplished in places like Egypt and Afghanistan? The culmination of a decade puzzling over this question culminated in leading a team to develop a tool that measures reporters’ skills via content analysis scores, and I relished every minute of it.

So now, with another decade to go before I can retire, I’m contemplating whether it’s finally time for math to have an official role in my career.

I’ve been dabbling with statistics and data visualization off and on for the past year. Whenever I find time to pick it up, it still seems fun.

And I bet I could make a prettier, more interesting chart than this one.

In 1970, women were 3 percent of engineers, 14 percent of life and physical scientists, 15 percent of mathematical and computer workers, and 17 percent of social scientists. By 2011, women’s representation had grown in all STEM occupation groups. However, they remained significantly underrepresented in engineering and computer occupations, occupations that make up more than 80 percent of all STEM employment. In fact, women’s representation in computer occupations has declined since the 1990s. This mirrors the decline in women’s share of bachelor’s degrees in computer science awarded since the 1980s.

Women’s underrepresentation in STEM is a result of their significant underrepresentation in engineering and computer occupations, rather than math and science occupations. While women’s representation has continued to grow in math and science occupations since the 1970s, growth has tapered off in engineering since 1990. In 2011, women were 13 percent of engineers, 27 percent of computer professionals, 41 percent of life and physical scientists, 47 percent of mathematical workers, and 61 percent of social scientists.

Today is Day 100+20+3, which adds up to a penny from 2014 – when women earned just 19 percent of engineering and 18 percent of computer science bachelor’s degrees.