In October 1993, I had given up on men.

I was still recovering from the break-up of a long and disastrously passionate relationship that spring. Summer brought a series of brief mismatches and a suicidal bout of depression.

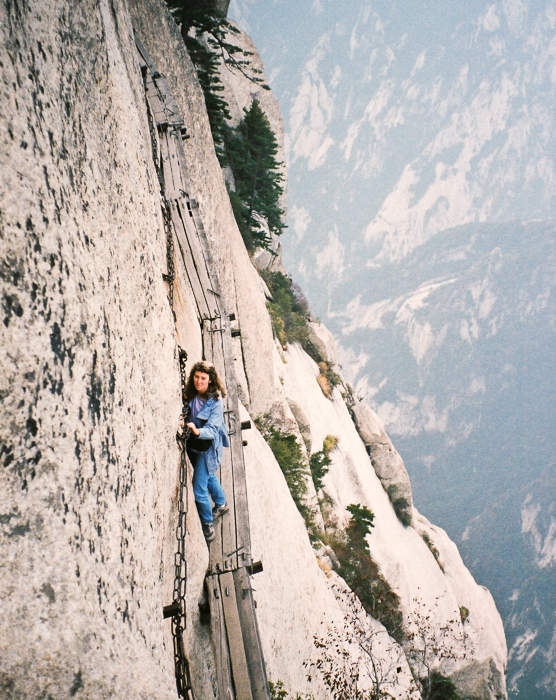

On top of Hua Shan in northern China that October, I stood exhausted from a grueling climb and exhilarated by the incredible view. The walkway led over a precipice hundreds of feet deep, and some Chinese tourists took photos of me.

It was the kind of moment where you want more than anything to have a lifetime partner with you.

That night, I accepted that I might spend my life alone. If I never meet the man who is right for me, then so be it.

Two days later, as I waited in the Beijing airport for a flight to Hanoi, there he was.

I noticed him across the lobby because of how he stood. Strangely statuesque for a man only 5’7”. A self-assured strength radiated from his compact body.

We introduced ourselves when we found that neither of us had an up-to-date guidebook. Vietnam was new to the tourist circuit then, and we were the only non-Asians on the flight.

It gave me pause that he was Israeli. I didn’t have particularly positive feelings toward Israel, because of its treatment of Palestinians. Though I’d dated Jewish men, when I pictured the man of my dreams in his various forms he was never Israeli.

By the time we changed money together in downtown Hanoi, Seffi and I were like old friends. Both restless spirits and writers, we quickly discovered a long list of obsessions in common that ranged from China to chocolate mousse.

We were never apart for 11 days through Vietnam.

When we flew from Danang to Saigon for the last leg of the trip, I fervently wished that the plane would crash. I did not want to imagine a life in which he was not at my side.

Seffi was a sabra, a native Israeli, born in Tel Aviv in 1947. “Sabra” means cactus, which defines the national character — prickly on the outside, full of life and nourishment on the inside.

Seffi had the toughness required of an Israeli man of that generation. Heavily scarred by three wars, he was muscled like a young athlete. But he could touch with gentle healing hands and played my body as though I were a cello. His sense of humor permeated whatever he did, without being juvenile or hurtful.

He was worldly as well as earthy — had traveled to nearly every interesting place I could name and many that I’d never heard of, and wore his cotton pants until they were only useful for fire fuel.

I watched him have an entire conversation with an elderly woman in a village, she speaking Vietnamese and he replying in Hebrew, and I swear they understood each other perfectly.

He drank his coffee thick and black and got by on a few hours’ sleep so that he had more time to read, eat, and make love. “Plenty of time to sleep when we’re dead,” he’d say.

He shared his eclectic scholarship with the unselfconscious delight of a second-grader. He could explain the flight path of an osprey or narrate the history of the Silk Road. All of it infused with the zest for life that bestows humor and grace every hour of every day.

Most of all, Seffi was thoroughly self-confident without being arrogant. He could trace his family lines back some eight centuries.

He knew exactly who he was, his place in history and in the world. That gave him the ability to be at home everywhere.

On the train ride from Hanoi to Hue, I watched him peel an apple. His knife curved steadily, making one long circular piece of red skin, and his concentration was pure and certain without being obsessive. It struck me that this was how Seffi moved through life.

It was the closest I’d ever been to seeing the Buddhist concept of enlightenment in a living person.

With him, I was completely myself because he was so much himself. In this new dimension, I accepted without question whatever time with Seffi was allotted to me, whether it was two days or 20 years.

When we parted finally, I did not expect to hear from him again. He was, after all, forever an Israeli, and he was finished with marriage. I ignored his promises that he’d write, and steeled myself for the empty mailbox.

He wrote, long letters as funny and warm and loving as he is. He sent copies of the magazines he’d written for and edited, and books about Israel and Jewish history. He talked of coming to visit.

Inspired by Seffi’s model of living on his own terms, I rode a burst of energy and confidence. I got acupuncture for my depression, I applied to graduate school and began taking classes, and I started training for a management job at the newspaper where I worked.

My interest in news and analysis about Israel was no longer a superficial one. At university I studied nationalism and Islamic fundamentalism with compulsion.

That June, 1994, Seffi came to Seattle. We spent two weeks touring the mountains and beaches of Washington State. I felt the same fullness I’d known with him in Vietnam.

In the San Juan Islands, standing next to Seffi on the shoreline of Puget Sound, I saw orca whales for the first time in my life. Over 10 years, ever since I came to the Northwest, I had longed to see them. That day they leaped into the air as though they were diving up to the sun.

Just before Seffi left Seattle, I asked if he were happy here. He said, “Every moment.”

I never heard from him again.

It doesn’t matter. I accepted him in his entirety, without reservation or condition, and even after he had abandoned me that feeling did not change.

Instead, like a near-death experience, the feeling of knowing him changed me. I glimpsed eternity, and it planted a calm pillar in my soul.

Three years after I last saw him, on a chilly April morning in 1997, I shouldered my bags in Amman, Jordan and headed for Jerusalem with an odd sense of pilgrimage.

Whether I would see Seffi there or not, I was at last coming to the place in the world that he loved as much as I loved him.

[To be continued…]

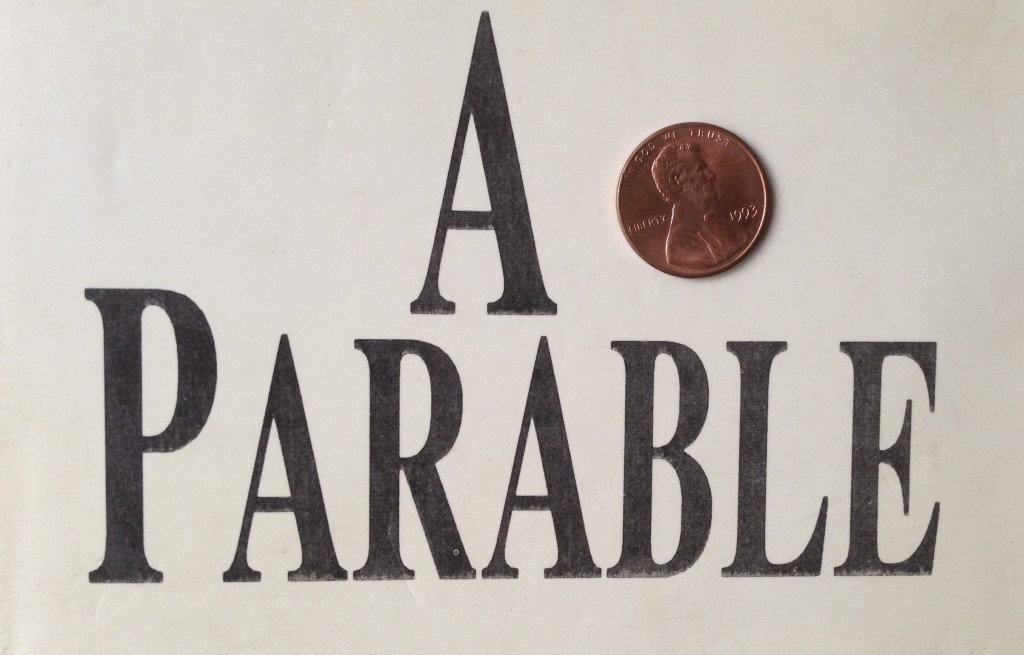

Day 108: a 1993 penny, for the year I met Seffi. The book is “Life As a Parable” by Pinhas Sadeh, which Seffi sent me that winter.

and how could you have never told me this story??? You need to write a screenplay. Next act please!!

Oh, well, actually I tried to write a screenplay, but the ending was too sad 🙁

Please don’t leave us hanging too long, even if it is a sad ending.