When we lose a memory, where does it go?

Inside the guts of a computer, the information is still there even if we can no longer activate it.

That must be why I’ve kept this decade-old Vaio laptop in storage for almost five years. Couldn’t bear to just toss it in the trash.

It holds days in Afghanistan, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt; hours working on airplane trays and wobbly desks; minutes Skyping across continents; seconds to tuck it smartly into a big purse.

Now: a warehouse in miniature.

But, like a warehouse, you need to know the paths and aisles to find what you need.

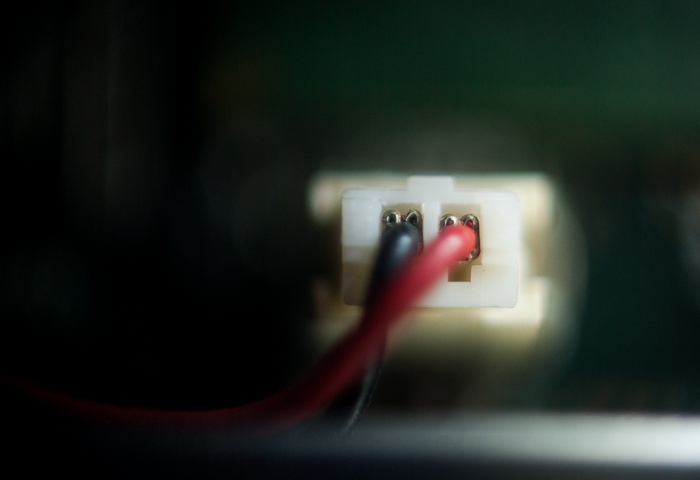

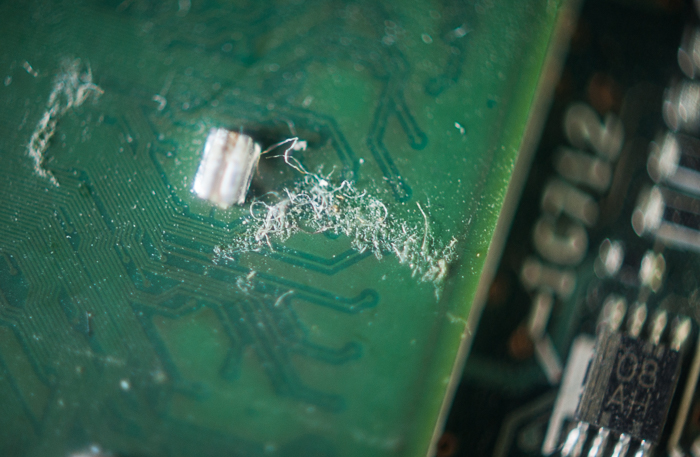

It’s there. When I open the Vaio, pull apart the layers and look into its guts, I feel it all again.

There’s a sticker on the top with the word for “computer” written in Arabic, a remnant of many hours studying that fluid and encrusted language.

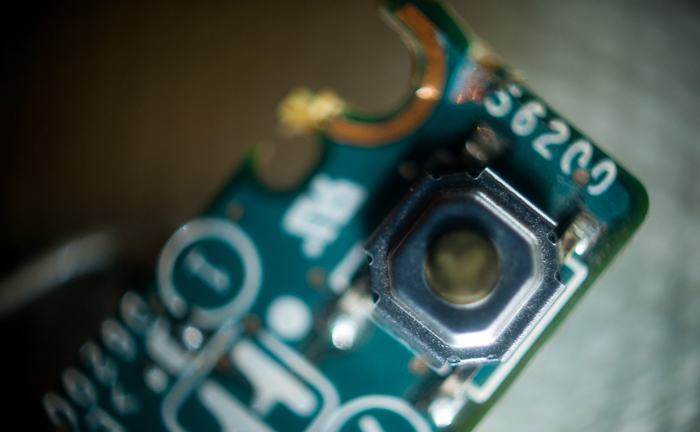

The power switch is circled with permanent marker and the word ON written next to it, a directive for a colleague still learning what a laptop was.

If only it were that simple for Afghans now.

The sandstorms. The haze that fell across our eyes and made time slow down, a veil of indelible impression.

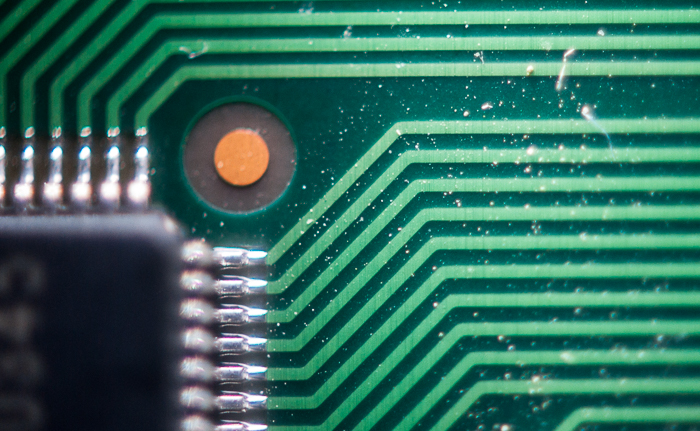

They say that the dust that accumulates inside a computer becomes magnetized, and thereby connected to the actual operation of the computer. Although any techie will tell you this is an urban myth, it has the mysterious power of gut-level truth.

Isn’t the dust of Dubai a part of me even now, thousands of showers later? How could I function without it?

How does memory find its way back up to the surface?

Buried in the depths for years, it leaps back to life with the smallest impulse, knowing the route along a map we can’t perceive.

We live in memory.

We eat its remnants, even as we kill the seed.

Weeds grow.

We survive.

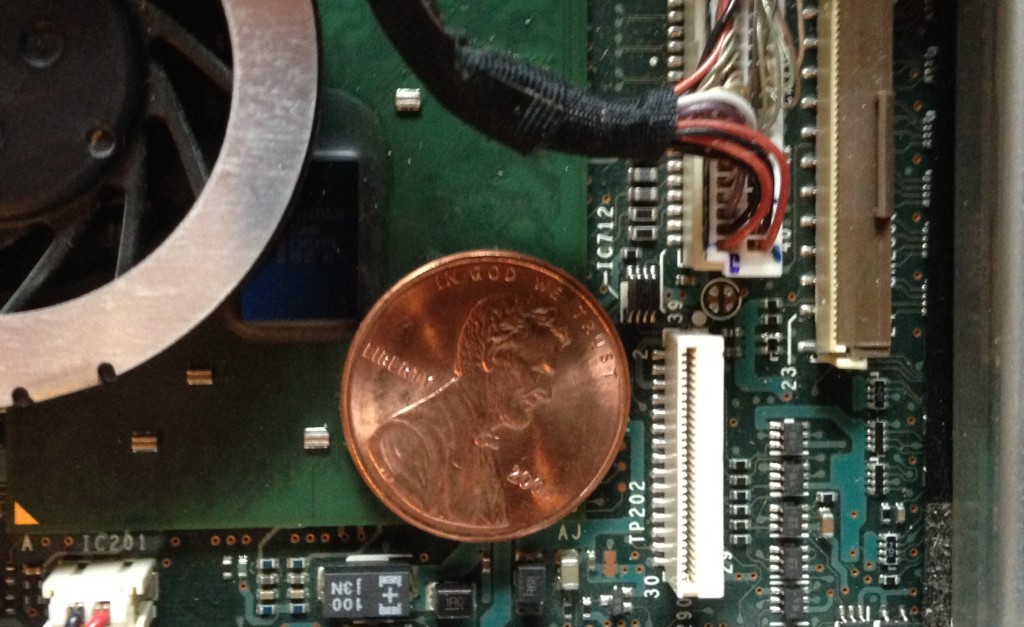

[For an explanation of how these photos were shot, see this post. I now call this technique hypermacro.]

Today’s penny is from 2005, which may or may not be the year I bought the Vaio. But it is the year I most associate with this laptop.