I was none too sure about you, Rob, when you sat down for the first day of orientation in Kabul.

April, 2004: We were setting up Pajhwok Afghan News, the first independent news agency in Afghanistan. There were 120 staff to whip into shape. We had just two months before we’d be publishing daily content, and only five months before the historic presidential elections which Pajhwok would play a lead role in covering.

It had been excruciatingly tough to recruit the 10 international journalists who would come to Kabul and work with those reporters and their editors.

We needed people who had experience working in countries where the bricks and mortar still hadn’t been picked up after the war. People who could tolerate intermittent electricity, irregular and slow Internet, and days without a hot shower. People who were so devoted to the profession of journalism that they would do anything, endure anything to help their colleagues.

On paper and in a chat interview, you seemed like someone who could handle those things. You had done an investigative reporting project in Slovakia and been kidnapped in Ghana. You said the right things.

On that first day, though, you didn’t like it when I pointed at your feet up on the desk. That was a classic taboo that foreigners often didn’t know: to show the soles of your feet was an insult to Afghans. In orientation, we held sessions to help the internationals avoid these gaffs.

You growled something and I thought, “Uh-oh. This is a guy who doesn’t want to change his ways.”

In the coming months, I saw you lose your temper a few times. That was hard on the young Afghans, who were still very unaccustomed to the tough newsroom style that we’d brought from America. You also had a fit or two in your daily struggles at the guesthouse we had set up – seemed like nothing ever, ever worked there, not the hot water or the electricity or the stove.

After the first three months, I asked the Afghan staff to evaluate the internationals. You got low marks for your angry outbursts.

When I sat down with you to discuss the results of the evaluation, I was very worried about how you’d take the criticism.

You listened earnestly and anxiously. You asked a lot of questions. And then said, “What can I do to improve?”

From that day on, you were absolutely a model trainer. You became the most-loved among the Afghans you mentored, exuding patience and caring, and never losing your temper.

When you got angry, you explained to them – every time – that it was your passion for the importance of the story that got you riled up. That you were tough on them because you cared so much about them.

They knew you meant it.

Gruff old editors in our era didn’t make a habit of saying nice things to young reporters. In Afghanistan, you learned how to do that.

The following year, when I was starting a project in Egypt, you were one of the first people I thought of to hire. As project manager, I was commuting from Dubai; you became the main leader on the ground.

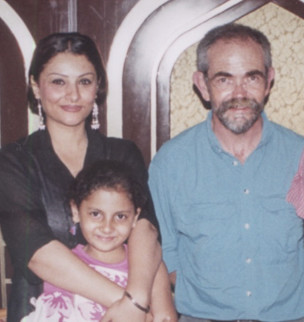

In Egypt you were equally loved. Your co-trainer, Eman, and the other colleagues on the team, both American and Egyptian, adored you.

It was still a very restricted era – and the 2005 presidential election, which we covered, had a field of candidates with not the slightest hope of defeating Hosni Mubarak. Under his iron reign, our reporters were terrified to stray anywhere near the red line. During the project they were followed, harassed, and thrown in jail.

We ran a website, interviewed Egyptian voters across the country, produced a printed voter’s guide to the issues, and did daily news coverage of the election.

I cannot imagine how we could have done it without your steadiness, your compassion, and most of all your unwavering devotion to journalism.

On Oct. 4, 2005, I was in the office of the UAE’s Minister of the Interior in Abu Dhabi on an interview. My phone kept ringing. It was a brand-new phone, and I didn’t even know how to silence it. Apologizing, I finally took out the battery.

Not until that evening did I find out what the persistent calls were about.

You must have known something was wrong as you sat at your desk, planning that day’s work. You must have laid down on the floor to see if that would help.

They found you that way.

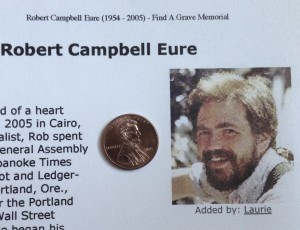

A heart attack, at age 50. You were a runner and had quit drinking more than 20 years before, but I guess the smoking got you in the end.

I think of all the cigarettes you inhaled to control your anger so that you didn’t yell at the Afghans.

Impossible that it’s been 10 years since that day. I still hear you over my shoulder when I am designing a new media development project, offering advice, pointing out sagely, “That’ll never work.”

I still miss you. And all the hundreds of journalists you’ve worked with, in a half-dozen countries, miss you, too. We still talk about you, still tell Rob stories. I love to tell the one about your reaction to your evaluation by the Afghans.

Whenever I laugh with a new group of colleagues, I hear you laughing too.

And right now I can hear you growling, “This story’s too damn long!”

Rob Eure, Oct. 4, 2005

Beautiful tribute, Lisa.

Thanks, Mark. You would have LOVED Rob.