My choices in clothes just never seem to work out.

On the last day of kindergarten, Mom allowed me to pick what I would wear. I chose an emerald-green corduroy jumper with little evergreen trees all over it.

It was June, too hot to wear corduroy anything. But I insisted on being granted this privilege of choice.

As I waited for the school bus with the sun beating down on me, I realized why Mom had wanted me to wear something else. I felt stupid. The fun was ruined.

It’s a feeling that is painfully familiar now. It happens when I choose clothes based on what I like, without running it past my internal social-appropriateness monitor.

Five decades later, I am no longer sure what I really want to wear. I have stopped listening to myself.

In a small town, at our Catholic school, conformity in dress was extreme. In sixth grade, I was at my most vulnerable to those social pressures. A certain T-shirt dress in red, white and blue was all the rage, and when I got one I became so cool that even a few of the really cool girls were, briefly, friends with me.

But the fashions changed, I couldn’t keep up, and I went back to being friends with the geeks and bookworms.

I kept making my weird choices. Choices that I loved when I made them, and then made me feel bad when I looked around and saw that I was so different from everyone else.

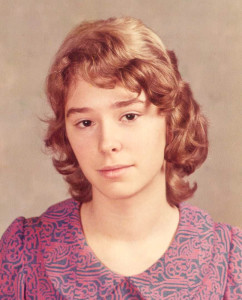

I got glasses in seventh grade that I thought were neat, but apparently made me look like an owl.

I had Mom make me a wrap-around skirt from woven fabric that had a Central American flavor, and people thought it was a throw rug. Then there was a dress in a blue fabric with orange humanoid figures squiggled on it, which I thought was fabulously artistic until someone said “What are those things on your dress?”

Conformity: In high school, I rolled up the plaid skirt of my uniform high enough to expose my thighs. Choice: When I got radicalized by feminism, I stopped rolling and even took the hem out so that my skirt was almost down to my knees. As though I needed more reasons for my lack of popularity with boys.

Once, in my late 20s, I got it right. For the company Christmas party, I chose to make a red satin dress from a Vogue pattern, with a tight bodice and a skirt so full that it extended wider than my outstretched arms. This was a hit when my husband and I showed off our jitterbug moves, and my skirt flew open to a big circle when I twirled, like a whirling dervish.

But we got divorced, and I never again found the right place to wear that dress.

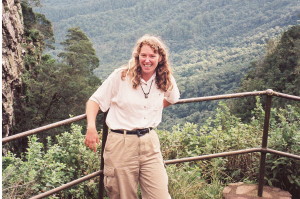

When I began to travel and work overseas, any semblance of choice got left behind in storage. By that time, I had learned at work that dressing in femme, flattering clothes only brought unwanted attention. It was hard enough to get through Africa and the Middle East with my blonde hair and 5’9″ stature; practical, durable, ugly clothes were the only way to go.

And in Afghanistan, keeping my skin and hair covered in public was an essential security precaution. I wore very baggy pants and long, Afghan-style tunics, like a man.

But when we lived in Dubai, I bought a few outfits that I really loved – the loose pyjama pants and long flowing blouses of Central and South Asia, adorned with colorful embroidery and sparkles and matching scarves. They were cool in the heat, flattering to my flabby middle, and never seemed too dressy or too casual.

The local population of Afghans, Pakistanis and Indians gave me thumbs-ups and seemed to love that I wore their style.

I only wore those clothes when I was out somewhere alone, though. It felt too awkward if I was around others from Europe and North America; they only wore the usual Westerner clothes. I don’t even have a photo of myself in those clothes.

Then we came back to live in the U.S., and wearing my Dubai clothes was out of the question. I felt far too conspicuous to wear them, except as a costume when I gave talks about Afghanistan.

I slumped into the anonymity of rural-poor clothes common to North Georgia: dollar-store jeans and Goodwill shirts.

If I truly could wear anything I wanted, it would be those clothes from Dubai. They are comfortable, beautiful, and expressive. Like the red satin dress, they make me want to dance.

But I can’t. Not even in a big city. The irony of America’s melting pot is that, while we have so many nationalities, if you’re not one of them you can’t wear their clothes.

I don’t want to appropriate someone else’s identity. Yet somehow, I can’t find my own.

Today’s penny is a 2006, for the year that I wore clothes I loved.